by Michael R. Allen

Yes, the much-mourned California Do-Nut Co. at 2924 S. Jefferson in Benton Park sports a storefront addition. The 1909 Sanborn fire insurance map shows the two-story building as a black smith shop, and building permits suggest that the addition dates to 1920. Here the addition seems to become part of a larger, mid-twentieth-century remodel. The parent building received a coat of stucco, the addition is clad in a Permastone-type material and the enameled neon sign board has an unmistakable modern swagger. The white and green color scheme is also sporty and simple, the hallmark of good mid-century design.

Yes, the much-mourned California Do-Nut Co. at 2924 S. Jefferson in Benton Park sports a storefront addition. The 1909 Sanborn fire insurance map shows the two-story building as a black smith shop, and building permits suggest that the addition dates to 1920. Here the addition seems to become part of a larger, mid-twentieth-century remodel. The parent building received a coat of stucco, the addition is clad in a Permastone-type material and the enameled neon sign board has an unmistakable modern swagger. The white and green color scheme is also sporty and simple, the hallmark of good mid-century design.

If the donut stands are doing well on Hampton and Watson road, why not Jefferson? Obviously, a little remodeling of that old store is needed, but the end result is an urban version of the roadside snack stand. Alas, a fabled reopening only led to plywood being hung on the storefront.

by Michael R. Allen

Here is another storefront addition, located at 3146 Shenandoah Avenue in Tower Grove East. The brightly-painted addition features brick pilasters at each side under a simple wooden cornice with decorative caps at each end. The addition is fairly respectful of the house behind it, allowing for a full view of its second and third floors and attractive brick cornice.

Here is another storefront addition, located at 3146 Shenandoah Avenue in Tower Grove East. The brightly-painted addition features brick pilasters at each side under a simple wooden cornice with decorative caps at each end. The addition is fairly respectful of the house behind it, allowing for a full view of its second and third floors and attractive brick cornice.

by Michael R. Allen

Once upon a time, on April 21, 1886, the city government issued a building permit for a continuous row of seven adjacent stores with flats above at 1121-33 N. Vandeventer. P.G. Gerhart was the developer of the $12,000 project. The result was a graceful building in the Italianate style. Striking cast iron columns supported the spans of each wide storefront opening. A wooden cornice capped the stone-clad front wall, and decorative brick corbelling continued the cornice line to a side entrance on Enright, above which the parapet wall formed a pediment to mirror the surround of the entrance. The handsome commercial row was located at a prime corner in the sought-after Midtown neighborhood, home of the city’s wealthy and middle class movers and shakers.

Once upon a time, on April 21, 1886, the city government issued a building permit for a continuous row of seven adjacent stores with flats above at 1121-33 N. Vandeventer. P.G. Gerhart was the developer of the $12,000 project. The result was a graceful building in the Italianate style. Striking cast iron columns supported the spans of each wide storefront opening. A wooden cornice capped the stone-clad front wall, and decorative brick corbelling continued the cornice line to a side entrance on Enright, above which the parapet wall formed a pediment to mirror the surround of the entrance. The handsome commercial row was located at a prime corner in the sought-after Midtown neighborhood, home of the city’s wealthy and middle class movers and shakers.

This was not the only such endeavor on Vandeventer, a major north-south artery here. Nor was it the Gerhart family’s only commercial row on the street. The presence of a street car line on Vandeventer along with the residential population of the area drew developers to an intensive building boom that lasted between 1875 and 1900. During that time, at least sixteen rows of adjacent stores like the Gerhart row went up. Most of these were two stories. Vandeventer must have had an urban character like no other street in the city, what with the effect of so many well-designed rows of shops.

Flash forward over 120 years, and the row is facing its demise in December 2008. After sitting vacant for a half-decade, the old row had ended up owned by someone who wanted it gone. The condition at the time of demolition was good, with no structural failures and all of the character-defining pieces still in place. The rise and fall and rising-again of Midtown had taken its toll on Vandeventer, depleting the stock of such rows to a handful by the dawn of the 21st century. Now the oldest survivor met its demise, and the street is poorer for it. Vandeventer north of Lindell Boulevard is marked by vacant lots and low-density new construction, with a handful of surviving historic buildings. This row was keeping its block on the good side of architectural wasteland status. Today, the site is yet another muddy lot adorned by spindly grass blades and blowing debris.

During demolition, wreckers from Bellon Wrecking staged work in accordance with the building’s party walls, leaving isolated sections standing untouched between areas that were demolished.

Architect Paul Hohmann photographed the demolition while it was underway, and has posted an extensive number of photographs here.

The loss of the row at Vandeventer and Enright delivered a sharp blow, but it was not the only one in 2008. In July, demolition commenced at the third of the surviving rows on Vandeventer, located at 1121 N. Vandeventer. The Guardian Angels purchased the site for construction of a new facility earlier in the year.

This row contained six storefronts arranged symmetrically along Vandeventer. The storefronts also had fine cast iron columns with Ionic capitals, and the second floor had arrangements of Roman-arched windows as book ends. This row dates to a permit issued on October 18, 1895 to Mrs. L.A. Crosswhite for six adjacent stores and flats. A.M. Baker served as architect, and Thomas Kelly was contractor. The row was totally vacant when I photographed it in 2006, but its loss was still jarring. Again, this stretch has lost its landmarks, and the site of this row is now another vacant lot with a sign promising new construction in the future.

Now the only remaining commercial row on Vandeventer is the Gerhart Block, developed by another Gerhart, at the southwest intersection of Vandeventer and Laclede. The Gerhart Block dates to 1896 and was designed by August Beinke. Its French Renaissance style has strongly eclectic traits and its historic integrity is stunning. The Gerhart Block and an adjacent building on Laclede Avenue were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2003; read the nomination by Lynn Josse here.

|

|

The sad fact is that this all that remains of the commercial rows of Vandeventer. There is some solace in that what survives is one of the most exquisite and well-preserved rows on the street, with landmark designation, demolition protection and tenants.

by Michael R. Allen

In 1966, the DeVille Motor Hotel became a Holiday Inn after the Vatterott family purchased the building. The modernist motel had opened in 1963 as part of the New Orleans-based DeVille chain, and was designed by renowned architect Charles Colbert. Although the motor hotel enjoyed a swanky reputation as the DeVille, its years as the Holiday Inn are its most famous among St. Louisans who recall dances and social events held in the public spaces. The postcard shown above dates to the time of the change in ownership.

In 1966, the DeVille Motor Hotel became a Holiday Inn after the Vatterott family purchased the building. The modernist motel had opened in 1963 as part of the New Orleans-based DeVille chain, and was designed by renowned architect Charles Colbert. Although the motor hotel enjoyed a swanky reputation as the DeVille, its years as the Holiday Inn are its most famous among St. Louisans who recall dances and social events held in the public spaces. The postcard shown above dates to the time of the change in ownership.

The rear of the postcard shows the new name: The Holiday Inn Midtown. Midtown was St. Louis’ Uptown, where the high-rollers mixed with the young professionals at the new lounges and restaurants of reborn Central West End. The spirit of optimism was high, and distinctly urban place names like “Midtown” were embraced as strongly as the idea that the city would rebound. The new Gateway Arch and Busch Stadium were signs of downtown’s new life, and the DeVille was a sign that the Central West End was as posh as ever for social life.

The rear of the postcard shows the new name: The Holiday Inn Midtown. Midtown was St. Louis’ Uptown, where the high-rollers mixed with the young professionals at the new lounges and restaurants of reborn Central West End. The spirit of optimism was high, and distinctly urban place names like “Midtown” were embraced as strongly as the idea that the city would rebound. The new Gateway Arch and Busch Stadium were signs of downtown’s new life, and the DeVille was a sign that the Central West End was as posh as ever for social life.

The end of the era was abrupt; the Holiday Inn Midtown closed in 1977, and was purchased by the Archdiocese for conversion to the San Luis Apartments (senior housing). Still, by 1977, Lindell Boulevard had attracted many new modernist buildings from Grand west to Kingshighway and the Central West End’s renewal was in full force. The DeVille was as sleek as ever, even with its less glamorous new use. Now that the San Luis Apartments are closed and the neighborhood’s stability is a sure bet, what better time is there to return the DeVille to its earlier glory? The old Bel Air Motel to the west, the city’s first motel dating to 1958, is posed to become a Hotel Indigo. The optimism about the city and the Central West End embodied by these buildings has paid off, and these mid-century landmarks have much to offer the present age as reminders of the power of architecture to convey the hope of an era.

(Postcard courtesy of Sheila Findall’s family collection.)

by Michael R. Allen

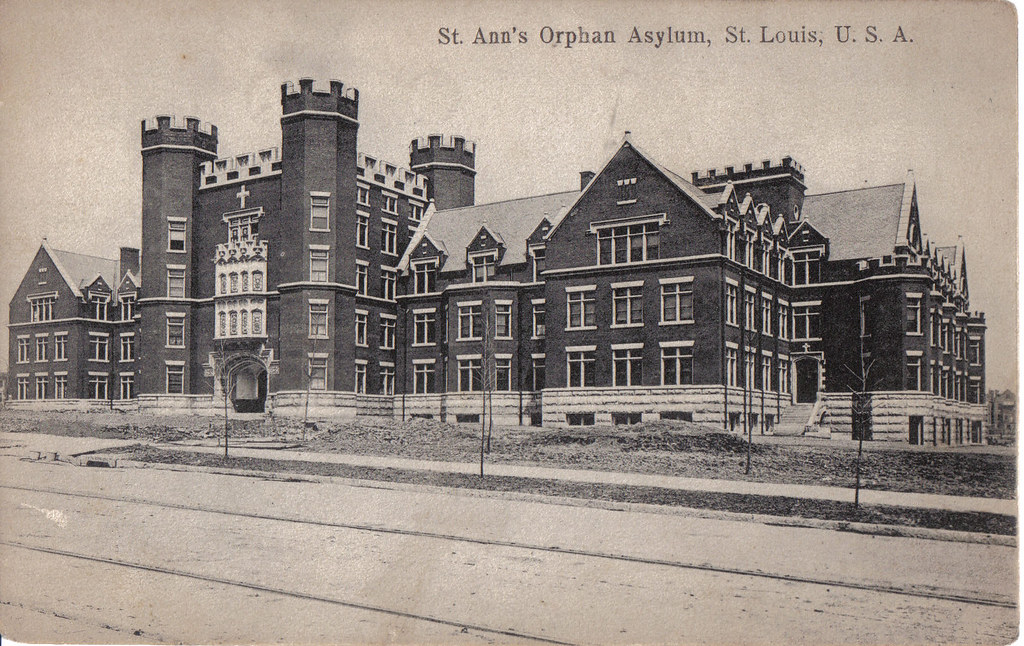

St. Ann’s Orphan Asylum stood at the northwest corner of Page and Union from 1904 until the late 1970s, when it was demolished. Operated by the Roman Catholic Church, the asylum relocated to the city’s west end from a downtown location at 10th and O’Fallon streets. The building permit dates to June 22, 1904 and lists a construction cost of $200,000 and the architects as Barnett, Haynes and Barnett.

St. Ann’s Orphan Asylum stood at the northwest corner of Page and Union from 1904 until the late 1970s, when it was demolished. Operated by the Roman Catholic Church, the asylum relocated to the city’s west end from a downtown location at 10th and O’Fallon streets. The building permit dates to June 22, 1904 and lists a construction cost of $200,000 and the architects as Barnett, Haynes and Barnett.

The high cost went for high quality. The 3 1/2 story asylum was large, and its Elizabethan Gothic architecture was elegant. The building featured an expansive lawn on four sides, affording the orphans with grounds for recreation surpassing the modest court at the downtown location. Here we see the late Victorian ideals — lovely architecture masking a function of social utility as well as a belief in the social and health benefits of planned open space. The asylum rose as the World’s Fair was taking place not far to the south in Forest Park. The fair reinforced the faith in planned open spaces and architectural grandeur found in the asylum. Coincidentally, the architects of the orphan’s asylum also designed the Palace of Liberal Arts at the fair.

In 1904, Barnett, Haynes and Barnett was one of the city’s best-known and most revered firms. The firm’s principals were George D. Barnett, John Haynes and Thomas P. Barnett, and together the men had already designed many homes and commercial buildings in the thriving west end. The firm also enjoyed a good relationship with the Archdiocese, an had designed the romantic Visitation Convent (1894, demolished) located at Belt and Cabanne in the West End, Sacred Heart Church (1898, demolished) at 25th and University in St. Louis Place, and the Scholastic Building at St. Louis University (1896). On Page Boulevard alone, the firm was responsible for designing St. Ann’s Church at Whittier and Page (1897) and St. Mark’s at Page and Academy (1901). The pinnacle of the working relationship would be the firm’s design of the great Cathedral Basilica on Lindell Boulevard. The firm’s institutional work shows a tendency toward the romantic, with picturesque buildings placed on landscaped lawns, and St. Ann’s Orphan Asylum fits in that range. Stylistically, however, the Elizabethan Gothic is unique for a large institutional building by the firm but parallel to the contenporary work of school architect William B. Ittner.

The asylum eventually became a retirement home before being demolished by the Archdiocese. The site today is occupied by the Annie Malone Children and Family Service Center and the Peace Villa, which maintain to some extent the site’s devotion to social service. The eastern end of the site is used by a grocery store.

(Postcard courtesy of the St. Louis Building Arts Foundation Library.)

by Michael R. Allen

Landmarks Association of St. Louis has published a position statement on the proposed St. Louis Public Schools facilities plan. Read the full text here.

The statement includes useful background information on the $200 million Capital Improvement Program that SLPS implemented from 1989 through 1991 in order to modernize buildings and abate lead and asbestos. The statement ends with wise and strong recommendations for protecting historic school buildings, reprinted here:

Historic Preservation

1. That District not demolish any school identified as historically or architecturally significant in the 1988 schools survey;

2. That the District place all eligible schools in the National Register of Historic Places to recognize their significance and to ensure demolition review under municipal ordinance;

3. That the District make all changes or additions to buildings (especially those included in the 1988 schools survey) respectful of defining architectural features and landscaped settings;

4. That the District obtain detailed bids from qualified contractors and architects with historic renovation work experience when evaluating the cost of retaining existing buildings, to avoid the assumption that renovating historic schools necessarily costs more than building new schools;

5. That the District consult with design professionals experienced in historic renovation work when making plans to renovate any existing schools included in the 1988 survey;

6. That the District develop, in concert with preservation consultants, a realistic maintenance plan for all the historic school buildings and incorporate them into a capital funding plan with rigorous follow through.

School Closures

1. That the District consider leasing schools to public or private entities as an alternative to sale;

2. That the District include in all sales contracts a clause forbidding demolition of schools included in the 1988 survey;

3. That the District reverse its policy of forbidding sales to charter schools or other educational entities, since such sale is preferable to abandonment or demolition;

4. That the District make every attempt to sell or lease buildings and avoid mothballing buildings, for the sake of neighborhood stabilization;

5. That the District properly secure and monitor any historic school closed but retained for future use.

by Michael R. Allen

In an article in today’s Peoria Journal-Star, Illinois’ new Governor Pat Quinn (D) pledges to reopen the closed Illinois state parks and historic sites. Furthermore, he indicates that he understands why the closures ordered by ousted Governor Rod Blagojevich (D) were foolish:

Nature-based and historic-based tourism are the fast-growing growing types of U.S. tourism, Quinn said. The dollars generated by tourism outweigh the cost of running the parks and historic sites, he said, adding that his administration somehow would find the money to reopen them.

“You squeeze a nickel and lose a half-dollar. That’s not smart government,” he said.

Quinn will reopen the closed sites “with dispatch.”

Kitty Kay Gloves

by Michael R. Allen

This morning I spied this sign in a storefront transom at 1235 Washington Avenue downtown (the building dubbed the “Avenida” by its developers). The sign reads “Kitty Kay Gloves: For Women Who C—–.” Kitty Kay was a popular twentieth century manufacturer of women’s gloves and accesories, but I don’t know how the tagline ends. Care? Count? Anyone know?

This morning I spied this sign in a storefront transom at 1235 Washington Avenue downtown (the building dubbed the “Avenida” by its developers). The sign reads “Kitty Kay Gloves: For Women Who C—–.” Kitty Kay was a popular twentieth century manufacturer of women’s gloves and accesories, but I don’t know how the tagline ends. Care? Count? Anyone know?