by Michael R. Allen

In September, I wrote about the storm-damaged collapsing eastern house in a row of three historic houses on the 2800 block of Lafayette Avenue (see “Rowhouse on Lafayette Avenue Slated for Demolition”, September 10). The Building Division quickly condemned for demolition the 19th century house as an emergency public safety hazard, and demolition commenced last month.

The result shows the pitfalls of our current policy for abandoned buildings.

There is no mistake that the wreckers hired by the Building Division did their job, but that job itself is not all that needed to be done. What is left behind by the crew an adjacent row house now weakened to a point where it too may start suffering structural problems. The first problem is that the side wall, of soft brick never meant to be exposed to weather, is now uncovered.

On the front elevation, as I predicted, the wreckers could not easily deal with the fact that the front wall of the row was laid as a continuous bond with no easy seams. The wrecking job led to loss of face brick and of part of the wooden cornice of the neighboring house. The loss of the cornice is inexcusable since a simple straight saw cut could have been used.

Again, I am not insinuating that the wreckers did anything wrong. Trouble is, they did what the city hired them to do. The city did not hire them to make sure the neighboring building was stabilized, or to do anything beyond removing 2804 Lafayette Avenue.

That task seems particularly short-sighted when one views the newly-exposed east elevation to find a gaping hole in the foundation wall. I have no clue how this hole was created, but I do know that it leaves wooden joists unsupported. Without support, those joists will eventually fall, and pull the walls downward with them. This hole should be patched in with masonry of either stone or concrete masonry units, but if anyone complains the most likely result will be that a city crew will cover it with plywood.

Clearly, the Building Division’s demolition policy leaves unresolved issues when one building in a row — and despite perceptions there are many row houses in the city — gets wrecked but the row stands. The neighboring house now has been destabilized and joist collapse, front wall spalling and other maladies will set in. Hopefully if it gets demolished, the occupied house next door will be protected from careless damage.

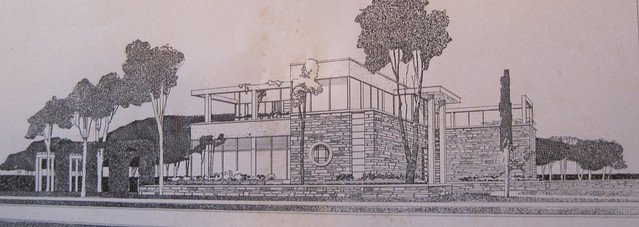

Photograph by Jane Porter of Landmarks Association of St. Louis from the National Register nomination of the Barr Branch Library Historic District, 1981.

Before the demolition, the potential of this fine row of houses on Lafayette reminded me of another row, also on the south side of Lafayette between Jefferson and Compton avenues. The photograph of Barr’s Block above shows its deteriorated condition in 1981. The seven-house row built in 1875 by merchant William Barr (of Famous-Barr fame) was in dire condition when it was listed in the National Register of Historic Places as part of the Barr Branch Library Historic District in 1982. That designation made the row eligible for the federal historic rehabilitation tax credit and led to the row’s rehabilitation. (One building was later demolished.)

Today Barr’s Block has been rehabilitated again, reverting to town houses from its previous incarnation as rental housing. While Lafayette Avenue in the Gate District may have lost building density and be marred by much vacant land, there remain many historic buildings and the potential for urban infill. The location is amazing. Why the row to the west — not part of any historic district — has been left to die is incomprehensible.